In 1987 Kiarostami made Where is my Friend’s Home?, a story about two young boys set in the remote Iranian village of Koker. The cast, including the boys, were all local villagers. In 1990 a massive earthquake in the same region killed 30,000 people, and Kiarostami set off to discover what had happened to the boys. Life, and Nothing More … is the film he made about this journey, a road trip by the director of Where is my Friend’s Home? and his son – and though these two are played by actors, the trip takes us through the actual disaster zone. In effect, it is a docudrama in which the director creates himself as a character.

The first half of the film depicts the slow, difficult trip along a highway choked with cars, lorries, moving equipment and rescue vehicles, through one devastated village after another. We see the driver and his son in closeup, from inside the car or through the windshield. We see crumbled buildings and people searching for victims and clearing up the debris, mostly filmed from inside the car. The audience is anchored in the car, hearing the conversation between the man and his son and his questioning of villagers and officials about the state of the roads ahead. Perhaps this is not the route to Koker, perhaps it is the route but impassable – but the driver persists. The filming of this section is strongly reminiscent of Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (1954) with its semi-documentary scenes of actors driving through real streets, alternating between shots of the actors in the car and ordinary street scenes shot from the car.

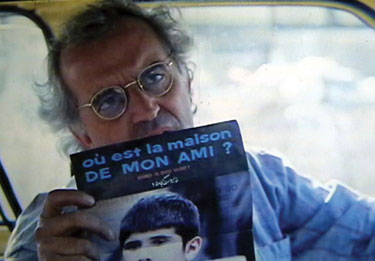

The driver asks people by the road if they know anything of the boys he is seeking. He shows them a photo on a movie poster; he’s from Tehran, the poster is in French, and he’s searching for two boys in a district where many thousands of dead are still being dug out of the rubble.

Finally, they leave the highway and attempt to reach the village by rough backroads, mostly deserted apart from occasional pedestrians carrying various bundles and items salvaged from the ruins of their homes. No longer hemmed in by other vehicles, the camera gives us the driver’s view through the windscreen and we see the bare, rocky landscape of northern Iran. The people they meet are courteous and helpful, yet is is obvious that the driver and his son are from a different world – the urban middle-class in the midst of the rural poor. Eventually, they reach a village in which part of the first film was shot, not far from Koker. The villagers are trying to carry on in the ruins, rescuing utensils, clothes and furnishings from what remains of their homes.

They meet an old man who played a character in Where is my Friend’s Home?, and he shows them a house – “that was my house in the movie” – and observes that his own house is in ruins. It’s better not to contemplate the intertextuality here – a real person who acted a character in another film is talking to an actor playing the part of the actual director of both films, and they are playing this scene amongst real devastation.

The son, who knows nothing of village life, clambers amongst the ruins: “Dad, what is this?” “A hearth.” “And this?” “An oven”. For the son, it’s all an adventure, the human significance of what has happened is simply beyond his comprehension. The father is determined to press on with his search, but he also tries to comprehend the effect the quake has had on the villagers.

He meets Hosein, a young man who has just been married, a few days after the quake. Hosein says that he had sixty-five relatives die under the rubble, but he and his fiancée decided to cut short the traditional mourning and marry. They slept three nights under plastic sheeting and have now moved into a partially ruined house. They want to go ahead and have children – who knows if they will survive the next quake? Better to get on with it.

The driver and his son continue, hoping to reach Koker. Unexpectedly, they encounter one of the boys they are seeking, walking along the road. He had been watching a World Cup match on television when the quake hit, and most of his family had escaped. They give him a lift to a temporary camp where survivors are staying. Men are putting up a TV aerial so that the survivors can watch the World Cup. The boy gets out and the driver’s son asks to stay to watch the match; since they are only a few kilometres from Koker, the driverr agrees and drives on alone.

Kiarostami is a poet of roads. The director/driver is already travelling the road when the film starts, and is still travelling at the end. The origin and the goal are purely notional, ideas that provide a frame for the film – but the road is the film.

“The road is the illustration of the soul that has no peace.” (Kiarostami).

Finally, the director is driving alone the last few kilometres to Koker. We have seen him drive on the choked highway, filmed claustrophobically in his battered yellow car, then on increasingly rough backroads, no longer threatened by traffic but battling the rough roads themselves. Now in the final, almost wordless sequence, he is struggling up a steep mountain road, trying to maintain traction. In extreme long-shot the car enters frame from the right on a level stretch, then turns to climb a steep grade. Near the top it loses traction and slips back a few metres. Again it climbs almost to the top, then slips and slowly rolls back to the bottom of the slope and stalls. A man carrying a bundle enters the frame and offers to help push the car, which starts and leaves the frame the way it entered. The camera follows the man with the bundle as he steadily climbs the hill to the top and turns onto a flatter stretch leading out of frame to the left. The camera pulls back to extreme long-shot and the car re-enters the frame, this time climbing all the way to the top and turning left along the road to Koker. It passes the pedestrian, then stops and picks him up and proceeds towards Koker as the film ends. This almost Sisyphean sequence elegantly encapsulates the spirit of the movie.

As they drive to her home, the conversation becomes prickly. This is not a reunion, he is only returning to Paris after four years to sign their divorce papers, and he had expected to stay at a hotel. Marie has two daughters by an earlier marriage, the teenaged Lucie and her sister Léa. When they arrive at the house, Léa is there, playing with a young boy, Fouad. Fouad is the son of Samir (Tahar Rahim, star of

As they drive to her home, the conversation becomes prickly. This is not a reunion, he is only returning to Paris after four years to sign their divorce papers, and he had expected to stay at a hotel. Marie has two daughters by an earlier marriage, the teenaged Lucie and her sister Léa. When they arrive at the house, Léa is there, playing with a young boy, Fouad. Fouad is the son of Samir (Tahar Rahim, star of